My time at a skiing startup: Carv

I spent 4 years at Carv as an Android Engineer. I’m now funemployed for the 3rd time, and I want to write about my time there, because there were some interesting moments, but mainly so its easier to recall when i’m applying for jobs in the future.

This is an honest, and sometimes maybe too open account of my experiences of work, fun, stress and skiing.

Preamble: Previous experience and learning projects

Before my stint at Carv, I was working for O2, a telecommunications company. I was doing backend Java development. Towards the end I got vaguely involved with some front end Android work and javascript/typescript type R&D projects. I enjoyed the nature of front end work, as seeing the code you were writing was satisfying. I liked it enough to decide to learn more about it.

At the start of my time at O2, I learned Java by writing a little flappy-bird-esque game, called OtterHopper (which is still on my GitHub for future comedy reference). I decided to re-write this in Android as a learning exercise. I did, and it was fun, so I immediately set about looking for a new, more challenging project.

WeClimb.Rocks

The project I settled on was to be called WeClimb.rocks. Named purely around an available domain weclimb.rocks, which I thought was cool. The idea was to make a crowd sourced database of climbing routes, where the USP was the ease of creating them. Simply take a photo of the rock, draw the routes on, and give them all names and grades and upload. All in-app. Easy. Nothing like that existed at the time and as far as i’m aware nothing exists to this day. The project is also on GitHub, although it has since been mothballed for reasons outlined in the readme.

I spent a lot of my spare time in my second year out developing this project, and i’m relatively proud of it. This project was the catalyst for me taking a new direction in my software career, from backend to app front end.

March 2020: Job Applications

I returned home from my second year out in March 2020. I had been traveling the southern hemisphere, for what was our winter and their summer. Australia, New Zealand and Bali. A fantastic 2 months, overshadowed only slightly by Covid. Luckily, I arrived home at the start of March, and the first lock-downs happened a few weeks later. I decided, since the world was going into lock-down that I should probably think about getting a job.

I applied for a bunch of roles, both in the Flutter and Android spaces at junior to mid level. If I remember rightly, a recruiter working for Carv found me on linkedin. I assume they took interest due to my profile photo. It was me on a mountain wearing a wooly hat. It screamed ‘mountain sports enthusiast’. I assume this because I had no relevant Android experience on my profile, so why else?

The interview process was long. Longer than any other company i’d interviewed with. I think they threw a few extra stages at me due to my lack of experience (fair enough).

I responded with my technical task and the message:

I think it’s safe to say i’m probably not what you’re looking for 🙂 I gave it my best shot, but I didn’t even get close to finishing the first exercise. … [some waffle about what i wanted to do had i the skills] … Thanks, and best of luck in your search!

However, i somehow passed that and the other 5 (yes really) stages, and was made an offer starting mid april. Happy birthday to me.

April 2020: Everything is broken. Help.

I started as you do any other job, setting up a laptop, meeting the team, joining calls and learning about what other teams did. I was impressed and horrified at the number of TLAs (three letter acronyms) being thrown around.

Testing the product

I was sent a Carv unit - the hardware that sits in your ski boot. In an attempt to familiarize myself with the product and what it actually did, I tried to set it up. At the time I had a Moto G5s+, a low end Android device gifted to me by a friend. My first experiences with the Carv product were not good. When attempting to pair the sensors to my phone, I received an error. A simple phone restart resolved this error, but it was a bad UX from the get go, and i was worried what i had signed up for. After successfully pairing the sensors, i found a bunch of other bugs while browsing the app. More nerves.

Customer Support

One fantastic thing about Carv is that the engineers are (or at least, were) on the front line of supporting customers. When I joined I was speaking to customers to diagnose their issues first hand. It was a stark change from my mega-corp job before, but it was somehow nice to hear the issues customers were having. It made me feel more responsible. However, it did add a new channel to the slowly building nervousness.

April 2020: Things are improving

It didn’t take long to feel like things were going in the right direction. By my 8th working day, I did my first release. 1.3.16 contained my first small bug fix, a small but major milestone for me.

From then on it was a case of find it, fix it and write a test to make sure it doesn’t happen again.

Summer / Autumn 2020 - New features begin

Along side the large amount of bug fixing I was doing, we still had goals to release some new features for the upcoming winter season. The first feature I worked on was the leaderboard. Adding the ability to filter by piste / resort / country and also allowing searching for people on the leaderboard. Additionally we refined a lot of the existing screens and flows to improve UX and UI. However, the split between investigating and fixing bugs and new features was quite heavy on the bug side. I was diving into areas i’d not dived before such as CPU profiling, memory leak analysis and debugging. Fun, but stressful when there’s a clear start to the ski season.

I was falling into the mindset of ‘everything is broken’ again, and the nerves and stress were ramping up.

December 2020 - Ski testing

Later than ideal, I flew out to Zermatt, Switzerland. I was performing some on mountain ski testing with a bunch of different devices we picked which were meant to cover a wide range of manufacturers, price points and OS versions. The trip should have been fun. I was being paid to go skiing! However, the trip was not fun. I was there for a total of 4 ski testing days. It was meant to be more, but I flew home early for reasons detailed below.

I was finding bugs. Lots of bugs. Bugs that weren’t straightforward to fix. Bugs that were hard to reproduce or debug.

The main standout in my memory is an issue we called ‘clock rollover’ internally, which you can read more about further down here. In summary though, this was an issue that would affect all the most recent Android flagship phones, and would render the Carv app useless. Fantastic.

I felt i’d spent the whole summer fixing bugs, and now so close to launch, i was finding so many more. It was demoralising and I remember lying awake in the apartment thinking i’d failed.

Health scare

As i was lying awake, thinking about my failures as a developer, my heart was racing. Additionally, it would occasionally skip a beat, which would result in a rush of adrenaline as i imagined my death-from-heart-attack, which in turn resulted in a hot flush. This would happen every few minutes or so. After a night or two of sleepless sweating and palpitations, i decided i had a heart problem and went to see a doctor in town. I walked in, flustered, and mumbled some words about my heart and its irregular beats. I was ushered over to a waiting area and very quickly seen by a doctor. He asked some basic questions, took my pulse and then left me in the room alone for what seemed like an hour. It was more like 5 minutes, and when he returned, he took my pulse again, smiled and asked me if i felt calmer. I did.

He asked me some more questions, about my job and stress levels. It was then that i realised what he was getting at. I didn’t have a heart problem, i was ‘just stressed’. I say ‘just stressed’, but the diagnosis was a panic attack. This was something i hadn’t experienced before so wasn’t aware of the symptoms.

The symptoms didn’t go away though, as i returned to the real world. I felt more dizzy, and just wanted to go home. So i did.

Support and understanding

Credit where credit is due, when i opened up about what happened and how i was feeling, everyone involved was very supportive, and most recalled a time where they’d had a similar experience. I was a little taken aback, that this was so normal.

Long lived android issues

After my freak out, and taking a few days off, i set to debugging some of those tricky issues i’d found on mountain.

To this day, there are 3 main issues that affect Carv on Android more so than Carv on IOS. They manifested to me while ski testing in Zermatt like so:

- The app would stop detecting skiing and therefore stop offering coaching tips

- The app would lose bluetooth connection to the sensors, and then the session timer would jump to a huge number

- The app would just die, randomly

My investigation, experimentation and analysis into these issues over the next 3 years turned into a support page about Android device compatibility. Here you can read a customer friendly description about the issues and also a phone recommendation list born from me analyzing over 175,000 skiing sessions.

There are three separate and more in depth support pages for each issue:

Unfortunately these issues likely won’t go away. Phone manufacturers are always going to produce low end devices, the SnapDragon 865 chip is in public use for the foreseeable, and the battery life arms race doesn’t show signs of ending any time soon. So as app developers we can only make customers aware of the issues as best we can.

I won’t repeat the information there here, so if you’re interested - go read. However i will dive into one of the issues in a little more detail.

SnapDragon 865 Bluetooth corruption

During my testing trip in Zermatt, I had access to a brand new Samsung Galaxy S20 FE, which was meant to represent flagship phones. Occasionally, the clock on the recording screen would jump to a crazy high number, and Carv would stop working. This was the SnapDragon 865 bluetooth corruption issue.

I wrote a fantastic (if i do say so myself) support article on this issue, which you can read here. It details an issue with the new (as of 2020) flagship SnapDragon 865 SoC’s, which were in all the flagship android phones that year. When this issue occurred, it rendered the Carv app useless.

I won’t repeat the details, so if you’re interested please give the article a read. However I did want to touch on the debugging process for this issue as i found it all rather interesting.

Bluetooth packet sniffing

This was foreign land to me. I’d only just learned the basics of how bluetooth communication worked between a peripheral and a phone. Now, somehow, i was purchasing a usb bluetooth sniffer, and installing wireshark.

This task was made extra difficult because there was no clear way to reproducing the issue apart from leaving the thing running and hoping it’d happen at some point.

Our theory of bluetooth corruption at the firmware / os level came from inspecting logs. This led us down the path of trying to prove that the bluetooth packet as sent by the peripheral (carv sensor) was different to the packet as received by the Carv app on the phone.

To do this, we needed to capture packets on both sides. The results of this debugging are best seen in my bug report to OnePlus on their public forum board.

In summary, we added a monotonically incrementing integer to the bluetooth packet structure, at the start and the end of the normal data. I wrote some magic wireshark lua scripts to pull this data out of the raw payloads to display in wireshark. I enabled HCI bluetooth snoop logging on the OnePlus phone and set wireshark to sniff bluetooth packets coming from the sensor i was debugging. I remember leaving this running overnight multiple times, often coming back to a crash, or an issue i didn’t foresee. Finally though, i came downstairs in the morning, bleary eyes, and saw the issue has been successfully reproduced. I skipped breakfast and checked both the sniffed packets and and hci snoop logs and low and behold - it worked. As seen in the bug report to OnePlus, the packet sniffed over the air from the Carv sensor had a sensible timestamp, whereas the same packet in the hci snoop logs, had a nonsense value. Proof!

I was momentarily elated, and put together a doc which turned into that bug report to OnePlus linked above. However, i knew, given the niche-ness of this issue that it probably would never be fixed. And i was right. Sadly, OnePlus went quiet on this issue yet again and it never got resolved. Oh well, i had fun digging into the lower levels of bluetooth.

2020-2023: Various GPS issues

Another area of pain was GPS, or should i say location. Carv uses location data to perform basic ski tracking functions: distance, descent, speed etc. There were 3 main issues with GPS data that i recall.

Constant horizontal / vertical accuracy

This issue affected only a small number of devices, mainly Samsung’s if i recall correctly. We never figured out why or in what circumstances this happened.

For context, Carv is picky about the location data it consumes. If the location data comes back with high accuracy values, it ignores it. This is to avoid inaccurate data causing zigzaggy skiing paths and inaccurate speed/distance/descent statistics.

These (mainly) Samsung phones would return ok-looking location data, but with an accuracy value above our threshold. This meant Carv discarded all the location data from the session. This obviously causes a bunch of issues with ski tracking functionality and is a very noticeable bug to have as a customer.

Given the small number of devices this issue affected and the inability to reproduce this issue, I decided to put in a dirty hack which removed the accuracy threshold, effectively letting all location data in, regardless of its accuracy.

Interestingly we never had any complaints from customers with this hack enabled that the app was showing bad tracking - indicating that the accuracy was actually lower than indicated.

Constant altitude data

The next and slightly more troubling issue was constant altitude. An issue i felt was severe enough to raise a bug into google. However, someone from wikiloc had beaten me to it. So i strongly +1’d their issue instead.

This issue was more widespread, and caused the altitude value to never change, or change very infrequently when using the FusedLocationProvider. As wikiloc point out in their original post, the LocationManager api works fine.

Google were fairly good in fixing this one. The issue was first reported Feb 2021, and they rolled out a fix later that month.

Spiky altitude data

The next season however, I started noticing more location related issues around altitude again. I decided to reopen the issue.

Backed up by a few more companies who make similar activity tracking apps, i was hopeful for another quick fix. I re-opened mid December 2021, and they acknowledged an algorithmic issue mid Jan 2022, saying it’d be rolled out early March 2022. In the mean time, we switched everyone over to the LocationManager API which continued to work ok.

However, this wasn’t the end of the saga. Next season (2022-2023), i decided to re-open the issue yet again as we were again seeing altitude based issues in customers location data.

This resulted in a long private email chain between myself and some google engineers. The end result was that spiky barometer data (probably) caused by pressure build up in the mostly-sealed pockets in a ski jacket, were causing issues with the fused output data. Unfortunately they weren’t able to prioritise fixing this for a while, but we had the LocationManager workaround so it wasn’t such a big deal.

2021: Hiring another android

Another new experience for me was hiring. In my previous role, i had done interviews along with a colleague. However i’d never run a hiring pipeline before, or acted alone in the interviews.

I remember reviewing my first few technical tasks, thinking “how have i ended up doing this”. A relatively junior developer, with about 1 years android experience is now reviewing other developers code, most of whom have many more years experience than me. Mad.

The most surprising thing for me was the time effort involved in hiring. Over the summer of 2021, i felt like i barely got any work done. Between task reviews, interviews and all the associated prep and admin, it was a long slog.

I was also surprised that i felt more nervous being the interviewer, than the interviewee. I felt more pressure to make the right hire for the company, whilst also not making a fool of myself in the interview. When applying for a job as an interviewee, there’s somehow less pressure, because you’re just doing it for yourself.

2021-2022: Move to subscriptions (QA madness)

The 2021-2022 season for me was all about subscriptions. Carv moved from being a one time payment for the hardware and app, to a one time payment for the hardware, and a yearly subscription for the app. This impacted many places around the app and the QA testing was complicated and long winded.

Way back when i joined, there was no record of what the app did, or should do. I came from a QA background, its how i started at O2, so this didn’t sit well with me. I created a spreadsheet, with manual acceptance tests in, to describe everything the app should do. I used this when testing releases, as documentation to show what had / hadn’t been tested. Every release had one and release notes linked to them.

As features for added, this simple spreadsheet grew and grew into a monster everyone feared to open. With the addition of memberships / subscriptions, the sheet grew so much it warranted a team wide discussion on how to deal with it. We tried and tested a few different options, but eventually settled on some small tweaks to the admin and layout of the sheet, splitting the tests by tab, and creating a new doc per release instead of a new tab. These simple changes solved a lot of the admin issues around modifying and finding tests, however the sheet still took a large amount of effort to work through.

We only tested everything once per year, before the main season release. All incremental releases were tested on an ‘as needs’ basis. The main season release would often take 1 - 2 weeks of QA and bug fixing to get ready.

“Why don’t you automate everything” i hear you scream. Simply put, the benefits didn’t outweigh the negatives at the time. The time burden of writing and maintaining end-to-end tests, was greater than the time it took to do manually. On both platforms we had a suite of end-to-end UI tests which tapped through the app as a user would, and checked certain scenarios. These were notoriously flaky, hard to setup, and took a large chunk of time away from developing new features. In the end, we decommissioned them and agreed on a manual testing approach for better or worse. I maintain that this was the right decision for where we were as a company at the time. Obviously, eventually the scales will tip and some form of automated testing will need to be adopted, but then wasn’t the time.

2022: Video Coach

One of the most satisfying features i built in the Carv app was Video Coach. For those who don’t know, Video Coach allows a friend to film a Carv user, and Carv will overlay a chart with turn by turn Ski IQ onto the video, allowing the skier to scrub through the video and see visually what their best and worst turns look like. The videos are also great for sharing and to show progress over time. Its a great feature, but there were some hurdles to cross in Android land.

Chart video overlay

A feature of the Video Coach videos is that they’re sharable. To be sharable we needed to export a sharable video from the component pieces: a video, a chart, and time. I remember IOS completing this piece of work very quickly using AVFoundation. On Android, there was no such API. At least, not at that high level. Through much research, i came across the MediaCodec APIs, grafika and bigflake. I went down a huge rabbit hole into the low level workings of these APIs, trying to cobble something together but ultimately, they defeated me and I couldn’t figure it out. I later looked at FFmpeg which looked promising, but again, i was defeated. I even started looking into OpenGL, but i’d sunk too much time into this already and there were more important things to do, so this project was parked.

Sadly, this is still one of a very few parts of the app where IOS and Android don’t have feature parity. Android users are suggested to screen record their videos if they want to share. Not ideal.

Frame by frame scrubbing

When the time came to create the Video Coach video player, with frame by frame scrubbing, i went down another big rabbit hole. We were already using ExoPlayer in the app for playing videos, so i decided to reuse this and try and make it scrub nicely. It didn’t and i spent way too long trying to make it work, before a colleague sent me this bug report suggesting that Android’s native MediaPlayer scrubs much smoother. I quickly switched to this and it was deemed ‘not great, not terrible’ aka, good enough to ship.

Cross platform bluetooth scanning

One surprise issue that was interesting to debug was the cross platform bluetooth linking issue. In order to link a video on the filmers phone to a skier, you need to ‘link’ to a nearby skier using bluetooth. To do this, the skiers phone is constantly advertising a specific ‘video coach’ service, which the filmers phone can detect and show some UI to link with this phone. If the skier is on IOS, and their app is running in the background, IOS doesn’t allow emitting bluetooth advertisements. This is a problem since we didn’t want to make IOS users take out their phone just to be able to be found in a scan.

We found a super useful blog by David Young about specifically this issue. Its an interesting read, but in summary it describes how to use the manufacturer data portion of a scan result to determine whether its an ios app in the background and whether its advertising the correct service. There’s also some helpful example android code which does exactly this.

Its not a perfect solution, as multiple service uuids would be detected as ‘the right one’ due to the vast number of 128-bit UUIDs flipping a single bit in a 128 bit bitmask, but it was ‘good enough’ as the chances some other device would be advertising a service that happened to flip the same bit were very slim.

Testing

Compared to other features i’d built, video coach seemed comparatively complicated to test. Sure i had unit tests for all the bluetooth scanning bits, but knowing android’s bluetooth stack, i had little to no confidence it would actually work like it should.

I devised a series of ‘dumb’ tests that would help put my mind at ease:

Video scrubbing smoothness

This test simply checked how smooth the video scrubbing appeared to be on a sample set of devices, where the filming device changed too. I wanted to do this because i had been developing on a relatively mid range OnePlus Nord, and video scrubbing was good enough, however i had a feeling it would deteriorate when a lower end device was used. I also wanted to check whether different filming devices output videos that scrubbed better or worse then others. For example, different devices output different video formats and resolutions. Would a 720p mkv scrub better than a 4k mp4. Probably but i had no idea.

I found that scrubbing seemed to be directly correlated to device performance, and that there was only slight variation in scrubbing performance for different filming phones, but nothing noteworthy.

Video lag

A complexity of video coach was how to sync the time between the filmer and the skier so ensure the video and skiing data line up correctly. We can’t trust the clocks on the device, so we devised a mechanism using bluetooth that i’ll spare the details on but essentially we send a bunch of timestamps back and forth between phones to calculate the time delta between the two.

Since this uses bluetooth, which is relatively slow in the context of millisecond precision video syncing, there was some margin for error.

Again knowing the android bluetooth stack, i wanted to be sure that this clock sync mechanism worked consistently on a wide range of devices.

To test this, we hacked video coach to graph acceleration instead of ski iq. This meant i could record a video session, smack the skier phone on a table, and when watching the video back, count the number of frames between the visible smack in the video and the smack in the phone acceleration graph. This if the ‘frame lag’ metric i was capturing.

The results were mixed, as expected, but ultimately the frame lag numbers came within a threshold that was deemed good enough that it would be hard to detect in the context of a video of someone skiing.

Advertise parameter testing

Android has some scary looking parameters when initialising bluetooth advertising:

- Interval

- TxPowerLevel

With such available values as high, medium and low i had no idea what to use. Battery consumption was a major concern for us when adding this constant advertising into the app, and i wanted to be sure i wasn’t unnecessarily draining customers batteries by using the wrong parameters.

val parameters: AdvertisingSetParameters = AdvertisingSetParameters.Builder()

...

.setInterval(bluetoothState.advertiseInterval)

.setTxPowerLevel(bluetoothState.advertiseTxPower)

.build()

Again, i devised some tests to check that each phone in my test arsenal could find and link to every other phone, gradually ruling out the worst configuration when something failed, and then moving onto the next level up.

After much testing i settled on medium tx power, and high interval. These settings allowed all test devices to be found by all other devices and i was less concerned about battery consumption now.

However I didn’t feel ok with only these findings. I wanted to test actual battery drain on the test suite of phones. To do this I manually started advertising, and left the phone overnight and checked battery consumption of the Carv app in the morning. I was pleased to see that the average battery drain was well within my expected threshold with the parameters i’d chosen. Nice.

GATT 133

In addition to the main 3 long lived android issues, there was GATT 133. Any Android developer who’s worked with the bluetooth stack is probably familiar with GATT 133. Its an error code, returned from some bluetooth operation that effectively says ‘sorry, something went wrong’. Tracing the real reason for failure from these errors is pretty much impossible, and they can happen for a bunch of different reasons.

This annoyed me so much for 2 years, that i decided to raise a bug report into Google to address the elephant in the room. Initially they appeared to push back that it was a real issue, and there was no activity for a long time.

However, 2 years after raising the initial bug (Feb 2022 -> May 2024), someone from google marked the issue as fixed. They link to the Android 15 beta 2 release notes, in which they note:

Also refined Bluetooth APIs for better developer experience and improved functionality. This includes fixes for GATT error handling

This came to nicely round off my time at Carv. May 2024 was my last month and it was a nice goodbye present from google. Its a shame i won’t be around to reap the rewards of hopefully less useless error messages, but i’m not complaining.

Maps

I love maps. I don’t know why, or where this love came from, but there’s something about the detail and intricacies of a map that make me a bit happy inside. I learned to read a map, acting as my mums sat-nat, before sat-nav was a thing. Remember when every car had a huge A-Z stuffed in the seat pockets? Maybe not, and i’m showing my age here.

I was lucky enough to work on a few map based projects in my time at Carv:

- OpenStreetMap migration inspector

- Internal piste & resort database

- Session debugger internal tool

- Custom mapbox style

OpenStreetMap Migration Inspector

All of Carv’s knowledge of the world, and the resorts, piste and lifts within it, come from OpenStreetMap. Think wikipedia but maps. Editable by anyone, for better or worse, OpenStreetMap was a goldmine of information about anything geospatial.

When i joined, Carv’s internal model of the world was built from a few GeoJson files made available by OpenSkiMap. OpenSkiMap is an open source web tool that ingests data from OpenStreetMap and does some clever magic to output sensible ski resorts, pistes and lifts, and displays them neatly on an interactive map. All the code is on GitHub if you’re interested. Its a truly fantastic project.

This was ok, however there was no way to update the information as changes came in through OpenStreetMap. Some years into my tenure, a colleague built a system in rust to ingest data directly from OpenStreetMap, cutting out the OpenSkiMap middle-man. This gave us full control of the rules we chose to combine the various data sets.

Re-importing data became possible, but it was anyone’s guess whether it was good sensible data or whether our rules worked. The best way to test was to import the data, load it into a custom mapbox style, and manually review changes. Given the data hadn’t ben updated for years, there were a lot (and i mean a lot) of changes. There was no way we could even sense check them. Additionally, to compare before and after the import you’d have to load the old mapbox style and new mapbox style side by side and play spot the difference. Blergh.

While i was working on the rust map data importer, i didn’t have any faith in my changes. I wanted a way to verify the changes were doing what they said they were, so i suggested a small web application. This web application would connect to a local database, which would be loaded with two data sets: the existing world view, and the world view after running the import. With this data, it would be possible to generate geojson to overlay onto mapbox in the browser, highlighting where resorts, pistes or lifts have been added, modified or removed.

The tool didn’t take long to build and when i got it working it was immediately obvious that there were a bunch of issues with the import code. So the tool worked well and is now in use every time data is imported from OpenStreetMap. Fun.

Session debugger internal tool

During my first year, if a customer came in with an issue related to maps, there was very limited tooling available. We had Jupyter notebooks that had access to the raw session data recorded on the phone. However, debugging in this style required some knowledge of the underlying data structures and python too. Debugging would ultimately sit with the dev team and this created a burden when dealing with customer issues.

To move this burden to the lovely customer experience team, we created session debugging dashboards using streamlit. These dashboards would give a useful overview of a customers session, allowing the customer experience team to debug certain issues themselves.

This worked ok, and the dashboards were relatively easy to build and maintain (if you knew python). However they were slow (really slow), and lacked continuity in the data. For example, the gps data was shown in 3 separate maps, and 2 separate graphs with different time axes. It was hard to mentally and visually join the data. “Like, i wanna hover over this gps path on the map, and i wanna see the gps accuracy, speed, latlng, etc”, said my brain.

For years, this niggled away at the back of my brain, but i never found the time to do anything about it.

However, every year Carv runs a developer hackathon after the ski season is well and truly done. Its meant to be for devs to work on cool features in the app that they want, but maybe aren’t the businesses top priority. The previous year i worked on a freestyle trick detector, which detects jump airtime and rotation. Sick. However, i kinda broke the rules this year as i wanted to work on a debugging tool.

I masqueraded the debugging tool as ‘Carv web view’ - see your skiing session on the web, with 3d maps and cool day playback! Sweet! However, deep down i knew the real purpose would be to help debug troublesome sessions.

I spent 2 days in the hackathon, hacking together a svelte web app. I built upon the framework of the OpenStreetMap Migration Inspector, and managed to get a working MVP done which rendered the sessions skiing and lifts on the map, with a sidebar showing the various stats like ski iq. My favourite feature was the day playback. A little location marker would fly over the screen, moving through the mountain as you skied in the day. I definitely didn’t steal this idea from Slopes.

I was pleased with the outcome and during my final month at Carv i was allowed to build the tool up to replace the old dashboards. This was potentially the most fun i had at Carv while writing code. Learning a new framework such as svelte and plotting data on a map, with fun interactivity was right up my street.

Closing note

This turned out to be a much longer blog than i was expecting. I guess i have a lot to write about due to the broad nature of the work i did at Carv. I really value that, it was a true ‘in at the deep end’ experience, but i learned a huge amount, not just through the work, but from the people around me to.

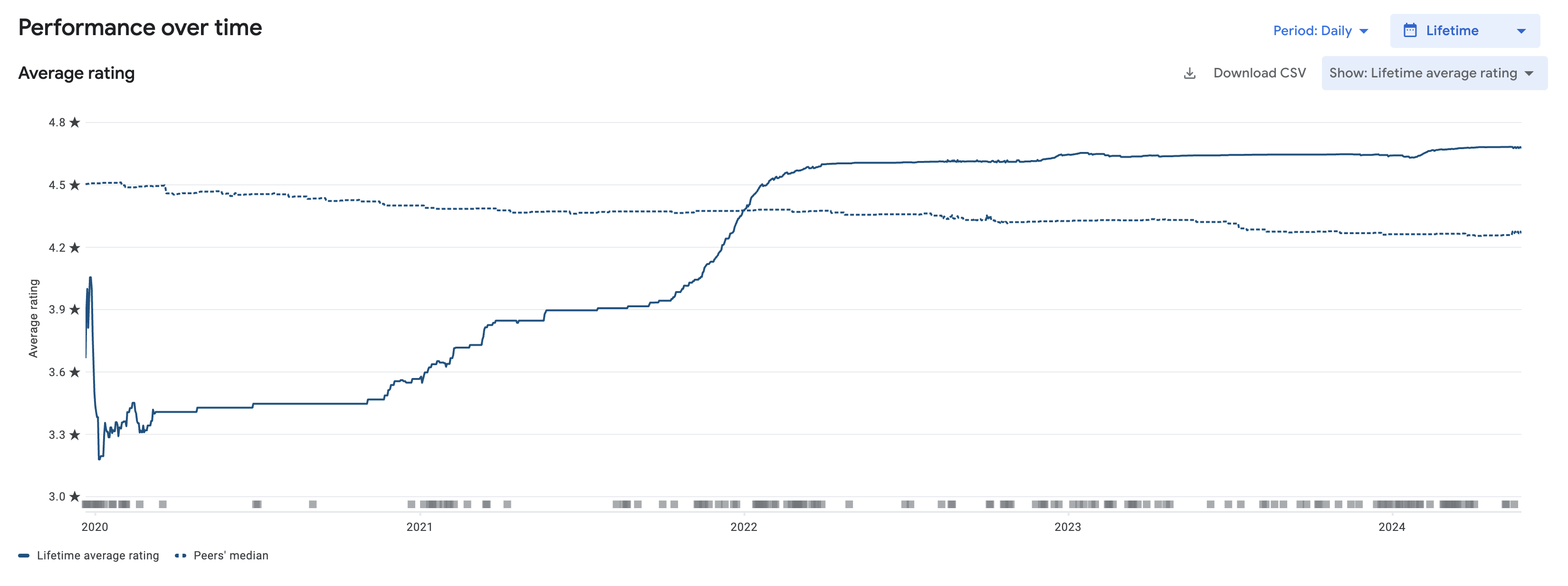

I’m proud to have had a positive impact on a sport that I love. Carv’s motto is that ‘skiing is more fun, the better at it you are’ - and i fully agree. I went from SkiIQ 139 in the 2020/2021 season, all the way up to 166 in 2024/2025. Carv definitely contributed to this improvement, and there are thousands of others around the world feeling that same impact. Nice.

There aren’t many pictures in this blog, but i’ll end with one i’m proud of.